Food Access

Pillar Navigation

- What Are the Issues Around Food Access in the Thunder Bay Area?

- Measures of income, poverty and homelessness

- Measures of consumption and nutrition

- Measures of food accessibility

- Measures of emergency food programs and usage

- Measures of participatory initiatives engaging people in their own food security

- What Do These Indicators Tell Us?

- Highlights

- References

GOAL

Build a food system based on the principle that food is a basic human right and that everyone should have regular and dignified access to adequate, affordable, nutritious, safe and culturally appropriate food.

What Are the Issues Around Food Access in the Thunder Bay Area?

The foods each person needs to live a healthy and happy life are part of a complex array of factors including connections to their community and culture. Food insecurity is described as “the inability to acquire or consume an adequate diet quality or sufficient quantity of food in socially acceptable ways, or the uncertainty that one will be able to do so.” 1 Food insecurity is directly related to inequity, financial constraints and is a marker of pervasive material deprivation. 2,3 In the Thunder Bay Area, far too many people do not get enough healthy foods and foods that they would prefer. Moreover, the rates of food insecurity are extremely disproportionate, with Indigenous and racialized people facing much higher incidences of food insecurity than the general population. This is not because there is a lack of food, but due to a failure of social structures, such as public policy, that have enabled this situation to persist and worsen over time.

A wide range of factors create barriers for people’s access to an adequate diet including poverty and inequity; social and geographic isolation; corporate concentration of the food system; the high cost of fuel; inadequate housing; heating and transportation costs; insufficient Ontario Works, Ontario Disability Support Program and minimum wage rates that don’t equate to a “living wage”; lost or fragmented food production and preparation skills; and lack of access to land for traditional hunting and gathering, to name only a few. Because secure access to a healthy and culturally appropriate diet is influenced by many factors, solutions must be broadly based and grounded in principles of social and environmental justice and a support for Indigenous food sovereignty.

A study conducted by Health Canada showed that household food insecurity is a significant social and public health problem in Canada. 4 According to PROOF, an interdisciplinary research program studying food insecurity, in 2021, 15.9% of households in the ten provinces experienced some level of food insecurity in the previous 12 months. That amounts to 5.8 million people, including almost 1.4 million children under the age of 18, living in food-insecure households”. 5 These estimates do not include people living in the territories or Indigenous people that live on-reserve, who are known to experience higher vulnerability to food insecurity.

An adequate and appropriate diet is central to physical and social well-being, dignity and autonomy. Food insecurity can lead to poor nutrition, mental health problems and increased risk of chronic and infectious diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer, as well as conditions such as low birth weight.

Measuring Poverty

Presently, the Canadian government does not have a standard definition of poverty, instead offering a variety of measures based on income-related terms including the low-income measure, the market basket measure, and the living wage.

What Is Market Basket Measure (MBM)?

The Market Basket Measure (MBM) of low income develops thresholds of poverty based upon the cost of a basket of food, clothing, shelter, transportation, and other items for individuals and families representing a modest, basic standard of living. A family with disposable income less than the poverty threshold appropriate for their family’s size and region would be living in poverty. Thunder Bay’s MBM is $44,340 for a family with two adults and two children. 6

What is Low Income Measure?

Presently, the Canadian government does not have an official definition of poverty, instead offering a variety of measures based on income-related terms. The Low Income Measure (LIM) is one such indicator of low income, and is used by Thunder Bay’s Poverty Reduction Strategy to determine how many people are living in poverty. It is calculated as 50% of the median income, adjusted for a family size. According to this measure, the LIM is $21,000 a year for a single person. This means that 12.8% or approximately 15,100 individuals in Thunder Bay live in poverty (have income under $21,000 a year). 7

What is a Living Wage?

A living wage is the hourly wage a worker needs to earn to cover their basic expenses and participate in their community. The living wage is not the same as the provincially mandated minimum wage which is $15.50 per hour for adults. The living wage for the North is $19.70. 8

MEASURES OF INCOME, POVERTY, AND HOMELESSNESS

Median total annual family income (after tax) of all low income family types in Thunder Bay (2022)

18,850

Measured: 2020

Source: Statistics Canada. Table 11-10-0020-01 After-tax low income status of census families based on Census Family Low Income Measure (CFLIM-AT), by family type and family composition – Thunder Bay 11

Unemployment rate in Thunder Bay CMA 8 (2022)

8.30%

Measured: 2021

Source: North Superior Workforce Planning Board. (2022). Setting the Course: Navigating the North Superior Workforce 2022-2023, page 31. 12

Households in the Thunder Bay District who receive social assistance benefits (Ontario Works or Ontario Disability) (2022)

8392

Measured: 2020

Source: The District of Thunder Bay Social Services Administration Board. (2020). TBDSSAB Quarterly Operational Report, 4th quarter. 13

Social housing vacancy rate in Thunder Bay (2022)

3.40%

Measured: 2020

Source: The District of Thunder Bay Social Services Administration Board. (2020). TBDSSAB Quarterly Operational Report, 4th quarter. 14

Active households on waitlist for social housing in Thunder Bay (2022)

756

Measured: 2020

Source: The District of Thunder Bay Social Services Administration Board. (2020). TBDSSAB Quarterly Operational Report, 4th quarter. 15

Number of social housing units in Thunder Bay (2022)

4290

Measured: 2020

Source: The District of Thunder Bay Social Services Administration Board. (2020). TBDSSAB Quarterly Operational Report, 4th quarter. 16

Number of people using emergency shelters in Thunder Bay – total unique individual stays (2022)

907

Measured: 2020

Source: The District of Thunder Bay Social Services Administration Board. (2020). TBDSSAB Annual Report. 17

Thunder Bay Census Metropolitan Area (CMA)

CMA refers to the municipalities of Thunder Bay, Oliver Paipoonge, Neebing, Conmee, O’Connor, Shuniah, Gillies, and Fort William First Nation.

What is Median After-Tax Income?

Median after-tax income means that you take the middle income and look at what that income would be after-tax. For instance, if you looked at incomes (before tax) ranging from $20,000, $35,000, $40,000, $45,000 and $50,000, the median would be $40,000. The median after-tax income would be $40,000 less applicable income taxes.

Nutritious Food Basket

Each year the Thunder Bay District Health Unit conducts the Nutritious Food Basket (NFB) survey, as mandated by the Ontario Public Health Standards. The survey is done in 6 grocery stores (5 in the city and one in the District) to price 67 food items to determine the lowest available price for healthy food. Over the last 10 years, the results consistently show that social assistance and minimum wage rates are insufficient to cover the cost of a basic nutritious diet after paying for other basic living expenses.

Why So Many People Can’t Afford Healthy Food

Have you ever wondered what your life would be like living on social assistance? In 2022 a family of four living on Ontario Works had a fixed monthly income of $2,780. According to the Thunder Bay District Health Unit, the cost of a Nutritious Food Basket for a family of four is $1,046. Let's talk about what that math looks like.

MEASURES OF CONSUMPTION AND NUTRITION

Percentage of citizens who consume 5 or more fruit and vegetable servings per day in the Thunder Bay District health region (2022)

29.7%

Measured: 2020

Source: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-625-x/2017001/article/54880/cma-rmr25-eng.htm 22

Measures of Food Accessibility

Cost of transportation – Single Cash Bus Fare (2022)

$3

Measured: 2022

Source: Thunder Bay Transit. (2022). https://www.thunderbay.ca/en/city-services/fares-and-passes.aspx 26

Cost of transportation: Monthly Bus Pass (2022)

$77.50

Measured: 2022

Source: Thunder Bay Transit. (2022). https://www.thunderbay.ca/en/city-services/fares-and-passes.aspx 27

Monthly cost of a nutritious food basket for a family of four (2022)

$949

Measured: 2021

Source: Thunder Bay District Health Unit (2021) https://www.tbdhu.com/resource/cost-of-eating-well-district-of-thunder-bay 28

Measures of Emergency Food Programs and Usage

Number of food banks (2022)

22

Measured: 2021

Source: Carlin, Brendan. (2022). Regional Food Distribution Association. Personal Communication. 29

Average number of people accessing food banks per month (2022)

3260

Measured: 2021

Source: Carlin, Brendan. (2022). Regional Food Distribution Association. Personal Communication. 30

Daily emergency meal programs available (2022)

5

Measured: 2022

Source: Thunder Bay and Area Food Strategy, Food Access Coalition. (2022). Where to Find Food in Thunder Bay Brochure. 31

Average number of meals served by emergency meal programs each month (2022)

14,279

Measured: 2021

Source: Carlin, Brendan. (2022). Regional Food Distribution Association. Personal Communication. 32

Measures of Participatory Initiatives Engaging People in their own Food Security

Number of Good Food Boxes sold (2022)

8324

Measured: 2021

Source: Scott, Sherry. (2021). Northwestern Ontario Women’s Centre. Personal Communication. 33

Number of Good Food Box host sites (2022)

40

Measured: 2021

Source: Scott, Sherry. (2021). Northwestern Ontario Women’s Centre. Personal Communication. 34

Number of schools with Student Nutrition Programs (2022)

51

Measured: 2022

Source: Hobbs, Daniel. (2022). Student Nutrition Programs, Canadian Red Cross. Personal Communication. 9

Number of people who participated in the Gleaning Program (2022)

65 (2019)

Measured:

Source: Ho, Ivan. (2022). Thunder Bay District Health Unit. Personal communication. 36

Amount of food gleaned (2022)

1747 lbs

Measured: 2019

Source: Ho, Ivan. (2022). Thunder Bay District Health Unit. Personal communication. 37

Pounds of meat distributed through the Wild Game Program (2022)

1235lbs

Measured: 2021

Source: Carlin, Brendan. (2022). Regional Food Distribution Association. Personal Communication. 38

Number of individuals served through through the Wild Game Program (new for 2022) (2022)

67

Measured: 2021

Source: Carlin, Brendan. (2022). Regional Food Distribution Association. Personal Communication. 39

Number of Mobile Market days (2022)

70

Measured: 2021

Source: McGibbon, Kim. (2022). Roots Community Food Centre. Personal Communication. 40

Number of Community Food Market locations (2022)

2

Measured: 2021

Source: McGibbon, Kim. (2022). Roots Community Food Centre. Personal Communication. 41

Number of Community Kitchen Programs available to the public (2022)

15+

Measured: 2022

Source: Ng, Vincent. (2022). Thunder Bay District Health Unit. Personal Communication. 42

Number of Community Gardens (2022)

17

Measured: 2022

Source: Ng, Vincent. (2022). Thunder Bay District Health Unit. Personal Communication. 43

Number of community garden plots (new for 2022)

388

Measured: 2022

Source: Ng, Vincent. (2022). Thunder Bay District Health Unit. Personal Communication. 44

What Do The 2022 Food Access Indicators Tell Us?

Food Insecurity is a Result of Inequity and Poverty

Food insecurity is primarily the result of inequity. This is most evident in the financial constraints too many people experience. Unprecedented inflation and rising costs of food, housing, transportation, etc.; coupled with economic uncertainty and rising interest rates means that many more people are struggling to put enough food on the table. All of the issues and concerns addressed in the 2015 Community Food Security Report Card with regards to Food Access are not only still prevalent today, but the situation has worsened for many people.

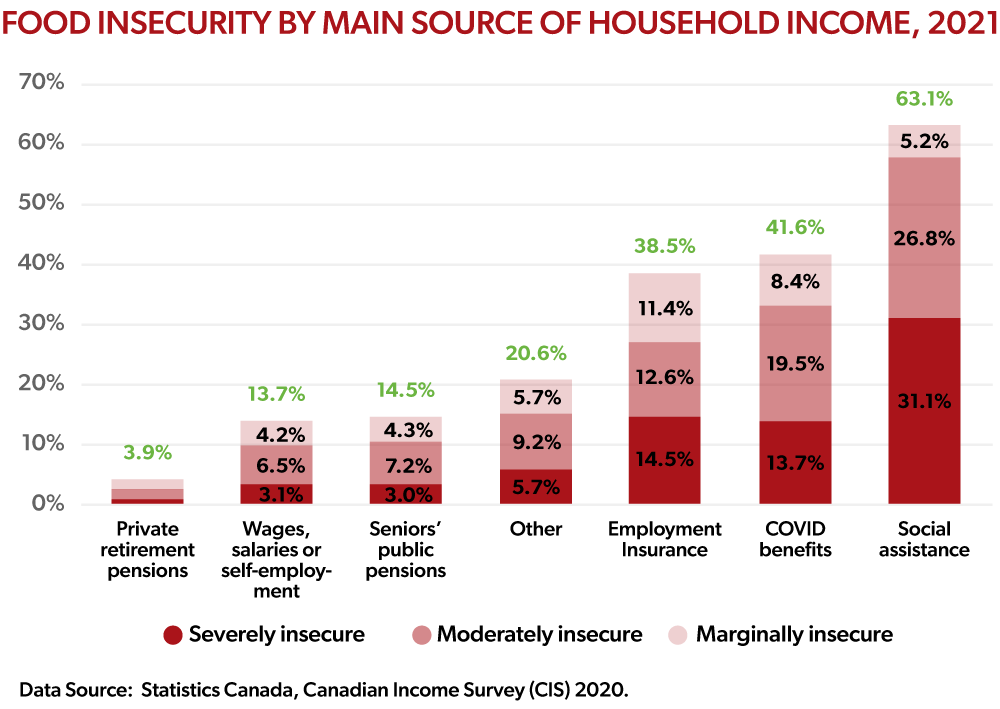

Households with lower incomes are more likely to be food-insecure. “Household food insecurity is a marker of material deprivation, tightly linked to other indicators of social and economic disadvantage.”45 In 2021, across Canada, one in seven households relying on employment income were food insecure, and households relying on employment incomes made up 51.9% of food-insecure households. Food insecurity was highly prevalent among households on social assistance (63% food-insecure) as well as those who faced job disruptions and had to rely on Employment Insurance (EI) (42%) or pandemic-related benefits like the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) (29%). Relying on any form of public income support except public pensions meant being very vulnerable to food insecurity. 46

Poverty is Worsening For Many

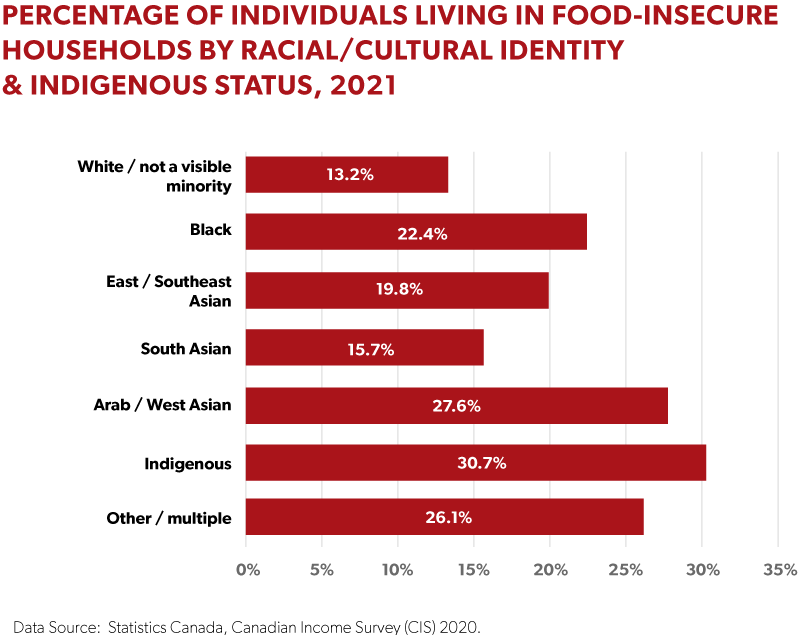

Local and national indicators show that poverty is getting worse for vulnerable populations. In 2017, it was estimated that 14% of the Thunder Bay population faced marginal to moderate food insecurity. 47 Anecdotal reports, as well as much of the data collected, suggest that this rate does not reflect the true levels of poverty in our community which is actually much higher. According to PROOF (see chart below) and echoed by the Thunder Bay Poverty Reduction Strategy (2022), some groups in our community experience poverty at a greater rate than others. These groups include: people earning their income on Ontario Works and Ontario Disability Support Program, Indigenous people, lone-parent families, new Canadians, older adults, women, racialized peoples ,and individuals with mental health issues and disabilities. 48 It is no coincidence that these groups also experience the highest rates of food insecurity.

Approximately 77% of single parent families in Thunder Bay are led by women. The research indicates that female lone-parent households have the highest rates of food insecurity - nearly double any other household demographic. In 2020, the Thunder Bay Poverty Reduction Strategy reported that the poverty rate for one-parent families headed by a woman with a child aged 0 to 5 was 31.3%, the highest among all family types, and more than five times the rate of couple-families with a child of the same age (6.0%) 49. These figures help to explain why one in five children is food insecure in Canada. 50

Racialization of Poverty

Better data collection and analysis in recent years is providing more accurate information about exactly who struggles with poverty in the Thunder Bay Area. According to PROOF’s national research (see chart below), Indigenous people have the highest rates of food insecurity—over 30%—in the country (this does not include people living in the territories or on First Nation reserves), followed closely by Black people and other racialized peoples/communities.

In the 2021 Census, Statistics Canada reports that 16,935 people identified as Indigenous (First Nations, Métis and Inuit) living in Thunder Bay. That is approximately 14% of the metropolitan area population. 51 However, the Our Health Counts Thunder Bay studies have shown that the Canadian Census undercounts Indigenous peoples living in cities and estimates that there are actually 43,359 Indigenous people living in the city of Thunder Bay which is over three times the number reported in the census. The study also determined that 89% of Indigenous adults in Thunder Bay fall below the before-tax low-income cut-off. 52 Local poverty data for Thunder Bay is collected through the Community Volunteer Income Tax Program (CVITP) annually. The 2021 data showed that 50% of participants living in poverty self-identified as Indigenous.

Food Banks Canada’s 2022 HungerCount Report also shows that Indigenous people accessing a food bank nearly doubled from 8% in 2021 to 15.3% in 2022. Indigenous households were already having to contend with high rates of food insecurity, and the combination of a reduction in income benefits and skyrocketing living costs in 2022 have had devastating consequences.53 The climate crisis is also impacting food security for Indigenous people by impacting availability of traditional foods, limiting access to hunting and fishing territories, and reducing the availability of ice roads that can be used to deliver food to remote and northern communities. 54

Additional Barriers to Food Access in the Thunder Bay Area

While inequity (and poverty) is the primary determinant of food insecurity, there are other factors that significantly impact food access. To fully understand and appreciate these barriers, a systems approach is required to identify the underlying factors that impact different people and groups. For example, Black and Indigneous people face much higher barriers to food access due to ongoing structural racism and settler colonialism. People living in rural and remote communities also tend to have less access to food and are forced to deal more directly with polluted waterways, toxic soils, and dwindling wild game populations. It is clear that while there is more than enough food in Canada to feed the population, not everyone has the same access to food. 55

Access to transportation is connected to both poverty and food. Focus groups and surveys conducted by the Thunder Bay + Area Food Strategy showed that, after the cost of food, lack of transportation is the next largest barrier to buying food. Although bus fares are on par to those of other Canadian cities, it is still a challenge for people with limited income to afford. People with small children or mobility issues also find it difficult or impossible to make trips to and from the grocery store using public transit due to limited routes and scheduling. As a result of anti-poverty advocacy, the City of Thunder Bay is piloting a reduced rate bus pass project for low-income riders in 2023 that will help to reduce the cost-of-transit barrier for some low-income residents.

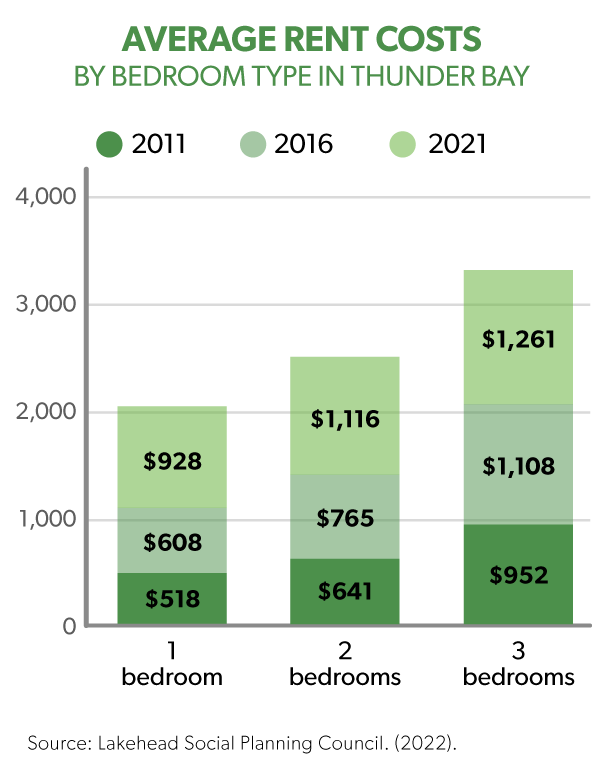

People facing insecure housing are also more likely to be food insecure. According to the Lakehead Social Planning Council, about half of individuals in Thunder Bay are homeowners, and half are renters. Homeowners spend much less than renters on average monthly shelter costs. While renters pay sometimes 75% of their income or more towards rent, only 9.1% of homeowners spend more than 30% of their income on monthly shelter costs. As the chart below indicates, the overall housing rental market has seen dramatic price increases in rent in recent years, further compounding the difficult affordability choices faced by those on low incomes.

Adequate and affordable meals require a safe place to store and prepare food. Many vulnerable people in Thunder Bay live in rooming houses, motels or temporary accommodations which have very limited cooking facilities, and therefore rely on emergency food providers. Data on homelessness has been difficult to capture during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anecdotal reports show that more people are facing homelessness and that there is insufficient housing supply, leading at times to encampments forming within the City. The real solution requires an increase in affordable and subsidized housing, along with appropriate supports to ensure successful long-term housing. While it appears that social housing vacancy rates and waiting lists have declined compared to 2015, these may be temporary gains resulting from increased funding during the COVID-19 pandemic. 56

Inequity and Poverty are Costly to our Health, Well-Being and Economy

Measures of consumption and nutrition have changed since the publication of the 2015 Community Food Security Report Card. Indications such as body mass index, used to quickly measure obesity, are no longer favoured as health indicators. These kinds of indicators are often not evidenced-based and serve to stigmatize and shame people. We know that only about 25% of the adult population eats more than the recommended five servings of fruits and vegetables per day. Adult and childhood rates of diabetes are also difficult to confirm.

Many studies show that communities pay a high price for the levels of inequity and food insecurity. Compared to the general population, food insecure households are more likely to have poorer quality dietary intake; fall behind in payments for phone, internet, utilities, and rent; live in overcrowded conditions and in housing in need of major repairs; and not fill prescriptions and not take medications as prescribed because of the cost. 57

Due to its effects on health, household food insecurity also places a substantial burden on our healthcare system and expenditure, while having a negative effect on the health of those living with food insecurity. For example, people who struggle getting food on the table also tend to use health care services such as doctor and emergency room visits more often. On average, a moderately food insecure household has health care costs that are 32% higher than more food secure households. 58 People living in food-insecure households are much more likely to be diagnosed with a wide variety of chronic conditions, diseases and infections, including mental health disorders. Further, “the relationship between food insecurity and health is graded, with adults and children in severely food insecure households most likely to experience serious adverse health outcomes. People who are food-insecure are less able to manage chronic conditions and therefore more likely to experience negative disease outcomes, to be hospitalized, and to die prematurely.” 59

Community Initiatives are Struggling to Fill the Gaps: Food Access Programs

Because income supports are insufficient for many to afford an adequate and nutritious diet, community organizations have stepped up to try and fill the gap. Food banks, initially introduced as a short-term band-aid to food insecurity, have become part of local food access infrastructure. Better data tracking and more support for food bank users has increased in recent years, helping to streamline registration and feed data into provincial food bank use statistics.

Food Banks of Canada’s 2022 Hunger Count Report found that demand for food banks was up 35% from 2019. Further, the demographics of food bank users show that one in seven people are currently employed; an astonishing 33% are children; 45% are from single-adult households; and 49% are reliant on social assistance or disability supports. 60 Feed Ontario’s 2022 Hunger Report observed a 42% increase in food bank visits from 2019-2021; and one in three were first time food bank users (a 64% increase since 2019). 61 Local food banks are reporting increased numbers and new users as well as increased demand overall.

Local emergency food programs such as the Dew Drop Inn also reported a dramatic 50% increase in the number of people accessing daily meals. Staff and volunteers report increased demand, especially from those living on fixed incomes. 62 Most agree that an increase in the use of food banks and emergency feeding programs show that hunger and food insecurity have become chronic, as people come to rely on charitable donations to stretch their monthly food budget. It’s important to note that only 20% of people who are food insecure access food banks. 63 There is insufficient data about what the other 80% of those facing food insecurity are doing to keep food on the table. Data collected by the Thunder Bay + Area Food Strategy about the emergency food response during COVID-19 found that some recipients of emergency food seek support from family and friends, “boosting” (shoplifting), and trading as ways in which they made up their shortfall in food access. 64

Community Initiatives are Struggling to Fill the Gaps: Community Initiatives

Locally, uptake for other community food access programs such as the Good Food Box, neighbourhood-based fresh food markets, and community garden involvement have increased in recent years due to ongoing food insecurity issues and the rising costs of food. The Good Food Box Program provides a box once per month of fresh produce, delivered to neighbourhoods at a subsidized cost. The number of host sites, number of boxes and households participating in the program has increased and demand continues to grow across all demographics including seniors, adults and children. Unfortunately, the increased cost of living is making it hard for many subscribers to afford their Good Food Box (approx. cost $22/month) without a financial subsidy. 65

There has been a concerted effort to target fresh food markets in specific neighbourhoods to increase fresh food access in these areas. To try and increase the uptake and affordability of fresh produce, one local community health centre is offering a “greens prescription” to patients to redeem at these fresh food markets. While the overall number of community gardens has decreased, there has been an increase in the number of plots, and there are more community gardens in development. Due to complications of the COVID-19 pandemic, gleaning and community kitchen programs saw a decrease in use, while the number of food hampers was increased in order to help households fill the gap (See the report Learning from Emergency Food Response during COVID-19 in Thunder Bay, Ontario). A number of neighbourhood-based community organizations, such as Our Kids Count, continue to offer important front line food and nutrition work with the children and families they serve. The wild game redistribution program continues to support individuals and families. All of these community initiatives provide benefits by increasing access to fresh produce, but they are not sufficient to meet all of the food security and dietary needs of participants - nor are they addressing the underlying causes of food insecurity.

Evidence-Informed Policy is the Solution

Accessing nutritious, culturally relevant foods remains a significant challenge for those earning low-incomes. Lack of income is the result of inequity and thus, a primary determinant of food insecurity - and the same income limitations are impacted by other costs including transportation, the high cost of housing and rent, and the stark increases in food affordability. Community food access and food literacy programs, food banks, and targeted fresh food markets and Good Food Boxes help support food access efforts, but they are not long-term solutions. “Tackling the conditions that give rise to food insecurity means re-evaluating the income supports and protections that are currently provided to very low income, working-aged Canadians and their families.” 66

Food Access Highlights

Dignified Food Access Guide

Roots Community Food Centre

Designed for staff and volunteers working with social service organizations who support people accessing emergency food.

Culture Kitchen

Roots Community Food Centre

A place for newcomer women to share their cooking with the local community and learn the skills and knowledge they need to start a food business from home.

Community Food Market & Greens Prescription Program

NorWest Community Health Centres, Roots Community Food Centre

A year-round fresh produce market offering wholesale prices to food insecure households.

Student Nutrition Programs

Administered through the Red Cross since 1997, Student Nutrition Programs offer food programs in 86 of the schools in the District of Thunder Bay and 52 in the Thunder Bay area. The large majority of the programs serve breakfast or a morning snack. The food is...

Good Food Box

The Thunder Bay Good Food Box is a monthly fruit and vegetable distribution program that aims to increase access to fresh and affordable produce in neighbourhoods, housing buildings, organizations, and participating First Nations year-round. The non-profit,...

2022 Food Access References

- Government of Canada. (2022). Household Food Insecurity in Canada. Retrieved from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/food-nutrition-surveillance/health-nutrition-surveys/canadian-community-health-survey-cchs/household-food-insecurity-canada-overview.html

- Mayer, T., & Anderson, M. D. (Eds.). (2020). Food Insecurity: A Matter of Justice, Sovereignty, and Survival. Routledge.

- Tarasuk V, Li T, Fafard St-Germain AA. (2022) Household food insecurity in Canada, 2021. Toronto: Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF).

- Health Canada, Office of Nutrition Policy and Promotion, Health Products and Food Branch. (2004). Income-Related Household Food Security in Canada.

- Tarasuk V, Li T, Fafard St-Germain AA. (2022) Household food insecurity in Canada, 2021. Toronto: Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF).

- Krysowaty, Bonnie. (2021). Thunder Bay Poverty Reduction Strategy: Building a Better Thunder Bay for All – 2021 Annual Report.

- Krysowaty, Bonnie. (2021). Thunder Bay Poverty Reduction Strategy: Building a Better Thunder Bay for All – 2021 Annual Report.

- Coleman, Anne and Shaban, Robin. (2022). Calculating Ontario’s Living Wages. Ontario Living Wage Network.

- Statistics Canada. 2022. (table). Census Profile. 2021 Census of Population. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-316-X2021001. Ottawa. Released December 15, 2022. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E (accessed December 30, 2022)

- Statistics Canada. 2022. (table). Census Profile. 2021 Census of Population. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-316-X2021001. Ottawa. Released December 15, 2022. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E (accessed December 30, 2022)

- Statistics Canada. Table 11-10-0020-01 After-tax low income status of census families based on Census Family Low Income Measure (CFLIM-AT), by family type and family composition – Thunder Bay.

- North Superior Workforce Planning Board. (2022). Setting the Course: Navigating the North Superior Workforce 2022-2023, page 31.

- The District of Thunder Bay Social Services Administration Board. (2020). TBDSSAB Quarterly Operational Report, 4th quarter.

- The District of Thunder Bay Social Services Administration Board. (2020). TBDSSAB Quarterly Operational Report, 4th quarter.

- The District of Thunder Bay Social Services Administration Board. (2020). TBDSSAB Quarterly Operational Report, 4th quarter.

- The District of Thunder Bay Social Services Administration Board. (2020). TBDSSAB Quarterly Operational Report, 4th quarter.

- The District of Thunder Bay Social Services Administration Board. (2020). TBDSSAB Annual Report.

- Lakehead Social Planning Council. (2021). Point in Time Count.

- Thunder Bay District Health Unit. (2022). The Cost of Eating Well in the District of Thunder Bay. https://www.tbdhu.com/resource/cost-of-eating-well-district-of-thunder-bay

- Thunder Bay District Health Unit. (2021). Hungry for Change in the Thunder Bay District. https://www.tbdhu.com/resource/cost-of-eating-well-district-of-thunder-bay

- https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-625-x/2017001/article/54880/cma-rmr25-eng.htm

- Thunder Bay Transit. (2022). https://www.thunderbay.ca/en/city-services/fares-and-passes.aspx

- Thunder Bay Transit. (2022). https://www.thunderbay.ca/en/city-services/fares-and-passes.aspx

- Thunder Bay District Health Unit (2021) https://www.tbdhu.com/resource/cost-of-eating-well-district-of-thunder-bay

- Carlin, Brendan. (2022). Regional Food Distribution Association. Personal Communication.

- Carlin, Brendan. (2022). Regional Food Distribution Association. Personal Communication.

- Thunder Bay + Area Food Strategy, Food Access Coalition. (2022). Where to Find Food in Thunder Bay Brochure.

- Carlin, Brendan. (2022). Regional Food Distribution Association. Personal Communication.

- Scott, Sherry. (2021). Northwestern Ontario Women’s Centre. Personal Communication.

- Scott, Sherry. (2021). Northwestern Ontario Women’s Centre. Personal Communication.

- Hobbs, Daniel. (2022). The Canadian Red Cross. Personal Communication.

- Ho, Ivan. (2022). Thunder Bay District Health Unit. Personal communication.

- Ho, Ivan. (2022). Thunder Bay District Health Unit. Personal communication.

- Carlin, Brendan. (2022). Regional Food Distribution Association. Personal Communication.

- Carlin, Brendan. (2022). Regional Food Distribution Association. Personal Communication.

- McGibbon, Kim. (2022). Roots Community Food Centre. Personal Communication.

- McGibbon, Kim. (2022). Roots Community Food Centre. Personal Communication.

- Ng, Vincent. (2022). Thunder Bay District Health Unit. Personal Communication.

- Ng, Vincent. (2022). Thunder Bay District Health Unit. Personal Communication.

- Ng, Vincent. (2022). Thunder Bay District Health Unit. Personal Communication.

- Tarasuk V, Li T, Fafard St-Germain AA. (2022) Household food insecurity in Canada, 2021. Toronto: Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF). Retrieved from https://proof.utoronto.ca/

- Tarasuk V, Li T, Fafard St-Germain AA. (2022) Household food insecurity in Canada, 2021. Toronto: Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF). Retrieved from https://proof.utoronto.ca/

- Ho, Ivan. (2022). Thunder Bay District Health Unit. Personal Communication.

- Lakehead Social Planning Council. (2013). Building a Better Thunder Bay for All: A Community Action Strategy to Reduce Poverty.

- Krysowaty, Bonnie. (2022). Lakehead Social Planning Council. Personal Communication.

- Tarasuk V, Li T, Fafard St-Germain AA. (2022) Household food insecurity in Canada, 2021. Toronto: Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF). Retrieved from https://proof.utoronto.ca/

- Statistics Canada. (2021). Census Profile: Thunder Bay.

- McConkey, S., Brar, R., Blais G., Hardy, M., Smylie, J. (2022). Indigenous Population Estimates for the City of Thunder Bay. Retrieved from: http://www.welllivinghouse.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/ohc-thunder-bay_pop-estimates-factsheet_final_1June2022.pdf

- Food Banks Canada (2022). HungerCount 2022. Mississauga: Food Banks Canada.

- Food Banks Canada (2022). HungerCount 2022. Mississauga: Food Banks Canada.

- Levkoe, C., Ray, L., & McLaughlin, J. (2019). The Indigenous food circle: reconciliation and resurgence through food in northwestern Ontario. Journal of agriculture, food systems, and community development, 9(B), 101-114.

- Krysowaty, Bonnie. (2022). Lakehead Social Planning Council. (2022). Personal Communication.

- Tarasuk, Valerie. (2022). Webinar: Food Insecurity in Canada in 2021. https://proof.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/PROOF-x-FSC-webinar-slides-2022-09-29-EN.pdf

- Tarasuk, V., Cheng, J., de Oliveira, C., Dachner, N., Gundersen, C., & Kurdyak, P. (2015). Association between household food insecurity and annual health care costs. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association Journal, 187(14), E429–E436.

- Tarasuk V, Li T, Fafard St-Germain AA. (2022) Household food insecurity in Canada, 2021. Toronto: Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF). Retrieved from https://proof.utoronto.ca/

- Food Banks Canada (2022). HungerCount 2022. Mississauga: Food Banks Canada.

- Feed Ontario. (2022). Hunger Report Final. https://feedontario.ca/research/hunger-report-2021/

- Quibell, Michael. (2022). Dew Drop Inn. Personal Communication.

- Tarasuk, Valerie. (2022). Webinar: Food Insecurity in Canada in 2021. https://proof.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/PROOF-x-FSC-webinar-slides-2022-09-29-EN.pdf

- Thunder Bay + Area Food Strategy. (2022). Learning from Emergency Food Response During COVID-19 Report.

- O’Reilly, Gwen. (2022). Northwestern Ontario Women’s Centre. Personal Communication.

- Tarasuk V, Li T, Fafard St-Germain AA. (2022) Household food insecurity in Canada, 2021. Toronto: Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF). Retrieved from https://proof.utoronto.ca/